The 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the War of 1812

Why did the country really go to war against the British? Which American icon came out of the forgotten war?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/82/32827c55-c567-4508-ae60-8fe37b647fc6/42-24017617-1.jpg)

1. The War Needs Re-Branding

“The War of 1812” is an easy handle for students who struggle with dates. But the name is a misnomer that makes the conflict sound like a mere wisp of a war that began and ended the same year.

In reality, it lasted 32 months following the U.S. declaration of war on Britain in June 1812. That’s longer than the Mexican-American War, Spanish-American War, and U.S. involvement in World War I.

Also confusing is the Battle of New Orleans, the largest of the war and a resounding U.S. victory. The battle occurred in January, 1815—two weeks after U.S. and British envoys signed a peace treaty in Ghent, Belgium. News traveled slowly then. Even so, it’s technically incorrect to say that the Battle of New Orleans was fought after the war, which didn’t officially end until February 16, 1815, when the Senate and President James Madison ratified the peace treaty.

For roughly a century, the conflict didn’t merit so much as a capital W in its name and was often called “the war of 1812.” The British were even more dismissive. They termed it “the American War of 1812,” to distinguish the conflict from the much great Napoleonic War in progress at the same time.

The War of 1812 may never merit a Tchaikovsky overture, but perhaps a new name would help rescue it from obscurity.

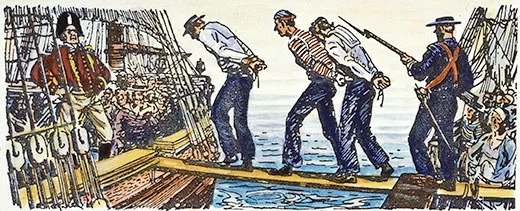

2. Impressment May Have Been a Trumped-Up Charge

One of the strongest impetuses for declaring war against Great Britain was the impressment of American seamen into the Royal Navy, a not uncommon act among navies at the time but one that incensed Americans nonetheless. President James Madison’s State Department reported that 6,257 Americans were pressed into service from 1807 through 1812. But how big a threat was impressment, really?

“The number of cases which are alleged to have occurred, is both extremely erroneous and exaggerated,” wrote Massachusetts Sen. James Lloyd, a Federalist and political rival of Madison’s. Lloyd argued that the president’s allies used impressment as “a theme of party clamour [sic], and party odium,” and that those citing as a casus belli were “those who have the least knowledge and the smallest interest in the subject.”

Other New England leaders, especially those with ties to the shipping industry, also doubted the severity of the problem. Timothy Pickering, the Bay State’s other senator, commissioned a study that counted the total number of impressed seamen from Massachusetts at slightly more than 100 and the total number of Americans at just a few hundred.

Yet the Britons’ support for Native Americans in conflicts with the United States, as well as their own designs on the North American frontier, pushed Southern and Western senators toward war, and they needed more support to declare it. An issue that could place the young nation as the aggrieved party could help; of the 19 senators who passed the declaration of war, only three were from New England and none of them were Federalists.

3. The Rockets Really Did Have Red Glare

Francis Scott Key famously saw the American flag flying over Fort McHenry amid the “rockets’ red glare” and “bombs bursting in air.” He wasn’t being metaphoric. The rockets were British missiles called Congreves and looked a bit like giant bottle rockets. Imagine a long stick that spins around in the air, attached to a cylindrical canister filled with gunpowder, tar and shrapnel. Congreves were inaccurate but intimidating, an 1814 version of “shock and awe.” The “bombs bursting in air” were 200 pound cannonballs, designed to explode above their target. The British fired about 1500 bombs and rockets at Fort McHenry from ships in Baltimore Harbor and only succeeded in killing four of the fort’s defenders.

4. Uncle Sam Came From the War Effort

The Star-Spangled Banner isn’t the only patriotic icon that dates to the War of 1812. It’s believed that “Uncle Sam” does, too. In Troy, New York, a military supplier named Sam Wilson packed meat rations in barrels labeled U.S. According to local lore, a soldier was told the initials stood for “Uncle Sam” Wilson, who was feeding the army. The name endured as shorthand for the U.S. government. However, the image of Uncle Sam as a white-bearded recruiter didn’t appear for another century, during World War I.

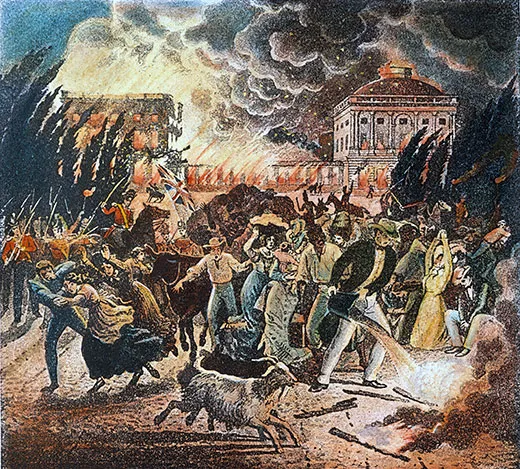

5. The Burning of Washington was Capital Payback

To Americans, the burning of Washington by British troops was a shocking act by barbaric invaders. But the burning was payback for a similar torching by American forces the year before. After defeating British troops at York (today’s Toronto), then the capital of Upper Canada, U.S. soldiers plundered the town and burned its parliament. The British exacted revenge in Aug. 1814 when they burned the White House, Congress, and other buildings.

Long-term, this may have been a blessing for the U.S. capital. The combustible “President’s House” (as it was then known) was rebuilt in sturdier form, with elegant furnishings and white paint replacing the earlier whitewash. The books burned at Congress’s library were replaced by Thomas Jefferson, whose wide-ranging collection became the foundation for today’s comprehensive Library of Congress.

6. Native Americans Were the War’s Biggest Losers

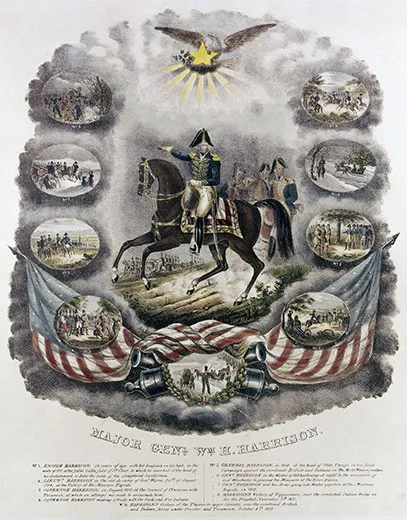

The United States declared war over what it saw as British violations of American sovereignty at sea. But the war resulted in a tremendous loss of Native American sovereignty, on land. Much of the combat occurred along the frontier, where Andrew Jackson battled Creeks in the South and William Henry Harrison fought Indians allied with the British in the “Old Northwest.” This culminated in the killing of the Shawnee warrior, Tecumseh, who had led pan-Indian resistance to American expansion. His death, other losses during the war, and Britain’s abandonment of their native allies after it, destroyed Indians’ defense of their lands east of the Mississippi, opening the way for waves of American settlers and “Indian Removal” to the west.

7. The Ill-Fated General Custer Had His Start in the War

In 1813, by the River Raisin in Michigan, the British and their Native American allies dealt the U.S. its most stinging defeat in the War of 1812, and the battle was followed by an Indian attack on wounded prisoners. This incident sparked an American battle cry, “Remember the Raisin!”

William Henry Harrison, who later led the U.S. to victory in battle against the British and Indians, is remembered on his tomb as “Avenger of the Massacre of the River Raisin.”

George Armstrong Custer remembered the Raisin, too. He spent much of his youth in Monroe, the city that grew up along the Raisin, and in 1871, he was photographed with War of 1812 veterans beside a monument to Americans slaughtered during and after the battle. Five years later, Custer also died fighting Indians, in one of the most lopsided defeats for U.S. forces since the River Raisin battle 63 years before.

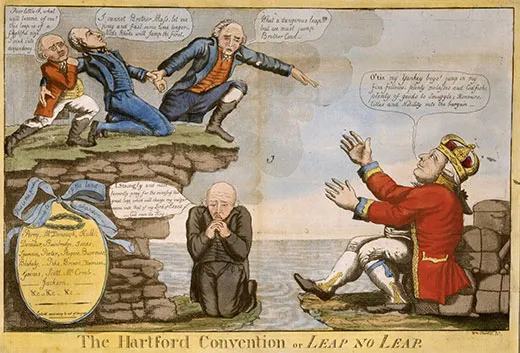

8. There Was Almost a United States of New England

The political tension persisted as the war progressed, culminating with the Hartford Convention, a meeting of New England dissidents who seriously flirted with the idea of seceding from the United States. They rarely used the terms “secession” or “disunion,” however, as they viewed it as merely a separation of two sovereign states.

For much of the preceding 15 years, Federalist plans for disunion ebbed and flowed with their party’s political fortunes. After their rival Thomas Jefferson won the presidency in 1800, they grumbled sporadically about seceding, but mostly when Jefferson took actions they didn’t appreciate (and, worse, when the electorate agreed with him). The Louisiana Purchase, they protested, was unconstitutional; the Embargo Act of 1807, they said, devastated the New England shipping industry. Electoral victories in 1808 silenced chatter of disunion, but the War of 1812 reignited those passions.

Led by Senator Thomas Pickering, disaffected politicians sent delegates to Hartford in 1814 as the first step in a series to sever ties with the United States. “I do not believe in the practicality of a long-continual union,” wrote Pickering to convention chairman George Cabot. The North and South’s “mutual wants would render a friendly and commercial intercourse inevitable.”

Cabot and other moderates in the party, however, quashed the secessionist sentiment. Their dissatisfaction with “Mr. Madison’s War,” they believed, was merely a consequence of belonging to a federation of states. Cabot wrote back to Pickering: “I greatly fear that a separation would be no remedy because the source of them is in the political theories of our country and in ourselves.... I hold democracy in its natural operation to be the government of the worst.”

9. Canadians Know More About the War Than You Do

Few Americans celebrate the War of 1812, or recall the fact that the U.S. invaded its northern neighbor three times in the course of the conflict. But the same isn’t true in Canada, where memory of the war and pride in its outcome runs deep.

In 1812, American “War Hawks” believed the conquest of what is today Ontario would be easy, and that settlers in the British-held territory would gladly become part of the U.S. But each of the American invasions was repelled. Canadians regard the war as a heroic defense against their much larger neighbor, and a formative moment in their country’s emergence as an independent nation. While the War of 1812 bicentennial is a muted affair in the U.S., Canada is reveling in the anniversary and celebrating heroes such as Isaac Brock and Laura Secord, little known south of the border.

“Every time Canada beats the Americans in hockey, everybody’s tremendously pleased,” says Canadian historian Allan Greer. “It’s like the big brother, you have to savor your few victories over him and this was one.”

10. The Last Veteran

Amazingly, some Americans living today were born when the last veteran of the War of 1812 was still alive. In 1905, a grand parade was held to celebrate the life of Hiram Silas Cronk, who died on April 29, two weeks after his 105th birthday.

Cronk “cast his first vote for Andrew Jackson and his last for Grover Cleveland,” according to a newspaper account from 1901.

After nearly a century of obscurity as a farmer in New York State, he became something of a celebrity the closer he came to dying. Stories about his life filled newspaper columns, and the New York City Board of Aldermen began planning Cronk’s funeral months before he died.

When he did, they marked the event with due ceremony. “As the funeral cortege moved from the Grand Central Station to the City Hall it afforded an imposing and unusual spectacle,” reported the Evening Press of Grand Rapids, Michigan. “Led by a police escort of mounted officers, a detachment from the United States regular Army, the Society of 1812 and the Old Guard in uniform, came the hearse bearing the old warrior’s body. Around it, in hollow square formation, marched the members of the U.S. Grant Post, G.A.R. Then followed the Washington Continental Guard from Washington, D.C., the Army and Navy Union, and carriages with members of the Cronk family. Carriages with Mayor McClellan and members of the city government brought up the rear.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)